Emancipation Day, the forerunner of Juneteenth celebrations, was observed in Virginia on various dates through the year, including Jan. 1 in Williamsburg.

Historic records also show that the day, sometimes referred to as Jubilee Day and Freedom Day, also was held on various dates throughout the South and the nation.

Elsewhere in Virginia, Emancipation Day also was held April 3 — the day federal troops took over Richmond — and on April 9, the anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

It’s not known when the local celebrations began after the Civil War, nor when they stopped, but New Year’s Day was the scene of large celebrations around the turn of the 20th century. The Richmond Planet, a Black newspaper, reported on a major Emancipation Day in Williamsburg on Jan. 1, 1897, the anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

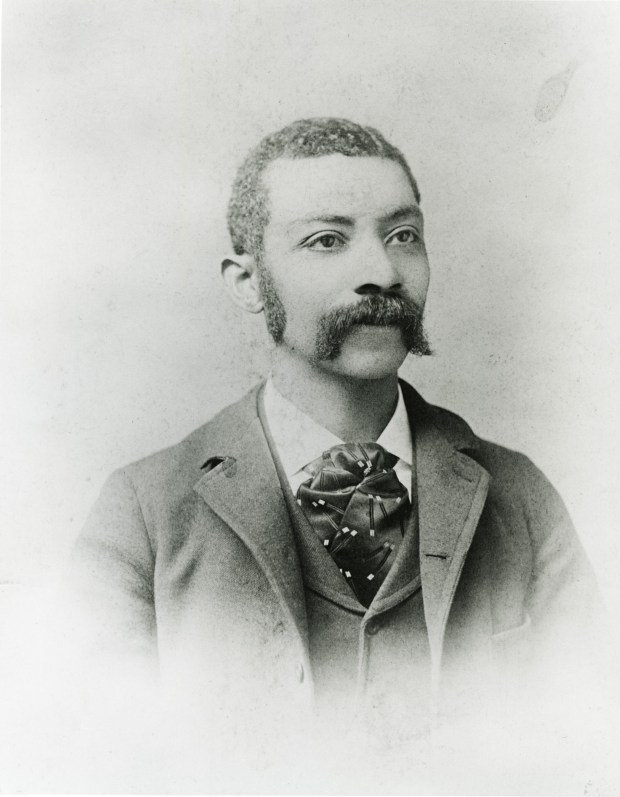

The chairman of the Emancipation committee was Samuel Harris, a businessman and entrepreneur and probably the wealthiest man in town. Earlier in the 1890s, Harris joined with Judge Richard L. Henley in the development of 417 acres north of the William & Mary campus. Later in 1897 he became a founding shareholder in the town’s first major bank.

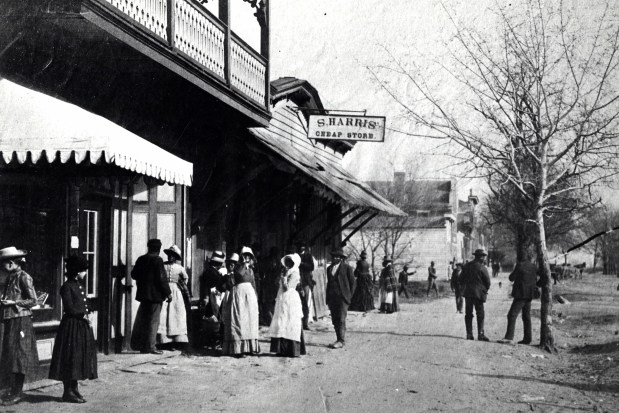

At the corner of Duke of Gloucester and Botetourt streets, amid what is now the Colonial Williamsburg Historic Area, was Harris’ central business — the Cheap Store — which offered an array of merchandise from dry goods and household furnishings and groceries to hardware, building supplies, horses and buggies.

“With the soft sunbeams from a clear sky, which was hailed with delight,” according to the Richmond Planet, citizens gathered in front of the Cheap Store to begin the Emancipation Day festivities. A “citizens cavalry” led by Harris gathered at the store “along with little and big horses, some prancing and some more dignified, all trimmed with red, white and blue.”

At noon a parade began headed by the cavalry and Normal School Band and carriages with out-of-town dignitaries including alderman Henry J. Moore of Richmond, President J. Hugh Johnson of the Virginia Norman and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University) in Petersburg and lawyer T. C. Walker of Gloucester, the day’s principal speaker.

Walker, known by some as “Virginia’s Black governor,” was the first African American to practice law in Gloucester County. Just before the 1897 exercises, he was appointed Virginia’s first Black Collector of Customs by President William McKinley.

One of the widest reported Emancipation Days was in Richmond on April 3, 1905, the 40th anniversary of the arrival of federal troops, the Washington Post reported. A Times-Dispatch editorial in its April 4 edition proclaimed, “Yesterday the colored citizens of Richmond observed ‘Emancipation Day’ and celebrated their deliverance from slavery by parading the streets, headed by a brass band and waving flags.”

In other smaller Virginia towns like Emporia, Clifton Forge and Boydton, Emancipation Day was celebrated with parades and speeches on April 9 to commemorate Lee’s surrender and the end of the Civil War.

One of the last large commemorations in Virginia took place on Dec. 31, 1944, on Jefferson Avenue in Newport News. The 3166th Quartermaster Service Company color guard and the 3167th Quarter Master Service Company of Camp Hill staged a parade on the eve of the 81st anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. There were also Newport News Shipyard workers’ floats. Camp Hill was operated by the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation and was located north of 64th Street between Jefferson Avenue and the James River.

The Loudoun County Emancipation Association continued to hold annual celebrations of the end of slavery at its fairgrounds into the second half of the 20th century.

Tappahannock also held a large April 3 celebration through the mid-1950s. There was a parade followed by a formal program in the Essex County Courthouse. Bessida Cauthorne White in her history of the county’s Emancipation celebration wrote:

“The fact that Black folk were able to keep the celebration going through the rise of Jim Crow, through the Great Depression, and through two world wars says much for the tenacity and perseverance of the African-American citizens of the area, and should not go unnoticed. It is ironic that a celebration that marked the fall of the City of Richmond was sustained in Tappahannock, but not in Richmond.”

Wilford Kale, kalehouse@aol.com

Check out was real simple, can't wait for the tote bag